California COVID-19 Crop Yields

Among the many negative impacts that COVID-19 has had on health, the economy, and social well-being there has been one well-documented silver lining. As states and whole countries issue stay-at-home orders, air quality has increased markedly. In California, which is home to 10 of the 25 U.S. cities with the worst levels of air pollution, improvements in air quality come as a breath of fresh air, both literally and figuratively, to the state’s residents.

But what do improvements in air quality mean for agriculture in the state? While intuitively the idea of cleaner air would mean better growing conditions for California’s crops, the truth is much more complicated.

According to a recently published study, poor air quality in California costs the state’s agricultural sector approximately $1b in lost yields every year. The study, which analyzed ambient ozone levels and crop yield data in California counties from 1980-2015, found that ambient ozone can have a significant effect on many of the state’s most lucrative crops. It does so by seeping into the pores of plants, essentially burning the cells that are responsible for photosynthesis.

How much of a negative effect does this ambient ozone have on crops? For many of the crops measured in this study, the researchers saw 5-15% decreases in yield attributable to the ambient ozone. Certain crops such as strawberries (2%), walnuts (3%), and hay (4%) see only slight decreases in yield due to ambient ozone, whereas others such as table grapes (22%), freestone peaches (11%), nectarines (9%), and wine grapes (7%) see much larger decreases in yield. The sensitivity of grapes to ozone is particularly notable because they are the most lucrative crop in California, bringing in $6.25B in receipts in 2018.

Caption: Geographical growing distribution of key California crops, courtesy of Hong et al.

This variation is in part due to the biological structure of the crops; certain crops are less sensitive to ozone, or not sensitive at all. But this variation is also a result of the different growing geographies of California’s crops. While the vast majority of agricultural products are grown in the San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys, the geographical distribution of production varies by crop. This is important because certain regions of California are exposed to much higher levels of ambient ozone than others.

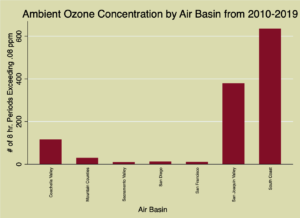

As the above graph shows, in the past decade, the San Joaquin Valley and South Coast air basins have had many more 8 hr periods in which ambient ozone levels have exceeded .08 ppm than any other California air basin. And while daily ozone averages for each air basin are unavailable for the past decade, so far in 2019 alone, the San Joaquin Valley and South Coast air basins have posted the highest daily average for ambient ozone levels.

Given this relationship between ambient ozone and crop health, a reduction in emissions due to COVID-19 would seem to spell good news for the state’s agricultural producers. Since statewide stay-at-home order was put in place on March 19th, NOx levels — one of the key chemical components of vehicle and industrial emissions — have dropped quite noticeably across many regions of the state. Unfortunately, these decreases in NOx haven’t translated into decreases in ambient ozone as well.

In fact, due to a peculiar chemical phenomenon called the “weekend effect,” decreases in NOx levels have actually led to slightly higher levels of ozone in certain areas of the state, namely the South Coast air basin. This is because NOx reacts with sunlight to create ozone but also helps break ozone down during cooler, darker weather. In essence, NOx produces ozone during the day but extinguishes it at night.

As of yet, improvements in overall air quality haven’t translated into decreases in ozone and thus improved growing conditions. But looking forward, scientists are grappling with how the stay-at-home order might affect ozone levels in the long term. Were NOx levels to remain low as we enter the hotter, sunnier months of the year it is possible that ozone levels would drop too. California climate scientists have credited stringent air pollution laws and improved emission detection technology for large declines in ozone since the 1980s. We can hope a similar effect will provide a silver lining to the COVID-19 episode.