Article by Sambhav Maheshwari

The COVID-19 pandemic, by changing experiences across transportation, well-being, caregiving, health care, and jobs, has caused society-wide shifts in behavior with potentially far reaching consequences. One of these is the impact on birth rates with potentially long-lived demographic consequences.

In 2020, many academics predicted that the incidence of a pandemic (COVID) would have a negative effect on birth rates. This is in line with a robust historical regularity that economic recessions lead to declines in fertility and birth rates. On the other hand, others noted that a pandemic coupled with a recession differs from a recession alone, and have hypothesized a baby boom, as people reproduce more while isolated and, in some countries, are kept economically comfortable by generous welfare state payments.

Demographic shifts have lasting, far reaching consequences across economics and society, hence our interest in the following questions. Does the severity of the COVID pandemic across nations have a significant effect on their births? Do people end up reproducing less knowing that they are in a global crisis, or more because of greater leisure time?

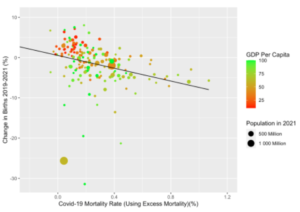

To address these questions, we create one visualization and estimate a multivariable regression. The figure plots the change in births against the cumulative COVID-19 excess mortality rate for 178 countries/territories. Excess mortality, using data from The Economist, refers to the number of reported deaths that exceed the expected deaths (Excess Mortality = reported deaths – expected deaths). Expected deaths are calculated based on comprehensive models that account for previous demographic trends. Excess mortality is superior to reported COVID-19 deaths because of cross-country differences in health infrastructure, testing, and reporting practices. Data on the % change in births across these 178 nations from 2019 to 2021 comes from “Our World in Data”. GDP per capita is displayed using a color scale using deciles (from red to green in order of increasing GDPPC), while population is illustrated by the size of the dot (a larger dot indicating a larger population).

Relationship between COVID Mortality and Births

The data exhibit a clear negative relationship between COVID-19 mortality (as a % of population) and the % change in births between 2019-2021. Countries suffering higher COVID mortality witnessed greater declines in fertility. Estimating a multivariable regression that controls for GDP per capita, we find that for each 1% increase in the COVID mortality rate, there is a negative 6.22% change in births (2019-2021). This would mean that a one standard deviation increase in the COVID mortality of around 0.2%, roughly the difference between Brazil and Peru, would lead to a 1.25% drop in births. We find that excess mortality explains about 15 % of the cross-country variation in the changes in births. Surprisingly, there is no difference between rich and poor countries in the COVID-sensitivity of birth rates.

The data include multiple outliers; countries with low COVID mortality but a significant negative change in their births from 2019-2021. One major example is China, where there was a COVID mortality rate of 0.04%, but a 25% drop in births. When we estimate a multivariate regression excluding China, we find a stronger negative relationship between COVID mortality and change in births across all other nations; a coefficient of -7.14. This means that for each 1% increase in mortality, there is now a negative 7.14% change in births. With this new model, we also find that COVID mortality accounts for about 20% of the variation in the changes in births. Other noteworthy outliers in this category include Hong Kong, Qatar, Aruba, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Azerbaijan, a majority (5/6) of which had strictly enforced lockdowns and restrictions. Thus, it would seem that restrictive policies that limit deaths result in fertility decline nonetheless.

In conclusion, our analysis reaffirms the prediction that more people either delay or skip having children in nations where the pandemic is worse. However, it is important to realize that our analysis only considers the impact of COVID mortality on individual decision making through March 2021. Because of the 9-month lag from pregnancy planning to birth, we will track with interest whether the 2023 figures show a rebound in births. Were births simply postponed leading to a higher than usual birth rate? Do we return to normal fertility implying those lost births are never to be replaced? Or does the fertility decline last beyond the incidence of the shock? Millions of potential lives are at stake.