Article by Noah Hendelman and Meghna Pamula

In March 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in the nationwide transition from in-person school to online learning. This transition resulted in a “learning loss” as students struggled with Wi-Fi trouble, screen fatigue, social isolation, and other consequences of remote education. Coming out of the pandemic, a prevailing narrative was that wealthier children and students who quickly returned to in-person instruction were largely isolated from learning loss. We seek to determine the extent to which variation in household income and length of school closure have affected learning loss among Southern California high schools specifically.

We use the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) to collect Math and English scores of students in 11th grade. We investigate how school reopening, income, and chronic absenteeism influence the change in Math and English test scores between 2018 to 2023. We assess the timing of school reopening by comparing Southern California counties with differing Covid-19 policies (Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego) to see if counties that permitted earlier school reopening were more sheltered from the learning loss. We also use local household income and change in chronic absenteeism to see how these neighborhood characteristics are related to the change in pre- and post-pandemic test scores.

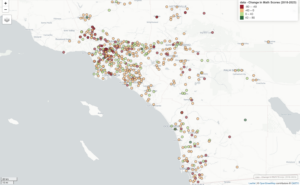

Map of Southern California High Schools’ Change in Math Score (2018-2023)

Score Range: Standard Not Met = 2280–2542 | Standard Met = 2628–2717 | Standard Nearly Met = 2543–2627 | Standard Exceeded = 2718–2900

Figure 1

Click here for an interactive version of this map.

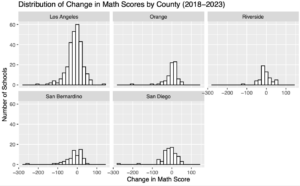

Figure 2 displays the distribution of the 2018 to 2023 change in Math scores across Southern California counties. Despite Orange and San Diego counties permitting sooner school re-openings than Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties, score distributions are statistically indistinguishable across counties. There are no statistically significant differences between counties in Math or English learning loss.

Figure 2

At first glance, these results may seem surprising: whether a county allowed schools to open within six months or well after a year made no difference in the learning outcomes of its students. But there are compelling explanations for this result. Policy directed at school re-openings was overwhelmingly concerned with Pre-K and elementary schools. In counties where early opening was permitted, many high schools–seen as the last priority to transition away from virtual learning–nevertheless remained remote as long as those in more-restrictive counties. Thus, the students differentially impacted by county reopening policies have not yet reached the 11th grade exams. We may see divergence in 11th grade CAASPP scores in upcoming years.

Moreover, while private high schools made more concerted efforts than their public school counterparts to reopen where permitted, they are not included in our data. These reasons may explain why we consistently find that county-level variation in school reopening policies is unrelated to learning loss among public high schools.

The effects of local income per capita are also surprising. According to our estimates, there is no statistically significant relationship between average per capita household income in the zip code where the school is located and the change in test scores. Contrary to the prevailing narrative, high schools in Southern California zip codes with a lower average income did not suffer greater drops in their test scores than high schools in richer areas. The pandemic did not discriminate with respect to income: neither schools with students from wealthy backgrounds nor schools with students from underprivileged backgrounds were shielded from the effects of the learning loss.

This finding is at odds with national studies, which conclude that school districts with higher family income were less severely impacted. The difference may be attributed to different level of schooling analyzed. While our data is at the high school level, other studies primarily focus on elementary and middle school learning loss. Students’ learning outcomes in primary education may be more dependent on parental investment as primary school students are less autonomous and their learning is more structured than that of high school students. The exclusion of private schools in our data may also have played a role in these results: wealthier families are disproportionately represented in private education, which fared better during the pandemic.

The sole factor in our analysis associated with a statistically significant change in test scores is chronic absenteeism, defined as missing 10% or more of instructional days. We find that over the 2018-2023 period, a 1% increase in chronic absenteeism is correlated with a 0.307 point decline in Math scores. In schools with rampant chronic absenteeism, reducing rates by 30% would improve learning losses in Math by over 9 points, over half the median decline induced by the pandemic.

However, these findings varied between subjects. Despite its relation to Math scores, chronic absenteeism proved statistically insignificant in its association with English scores. Still, because the brunt of pandemic learning loss came from a decline in Math (where the average score decrease was almost twice that of English), minimizing absenteeism will be crucial in addressing the subject most in need of assistance.

These results suggest that the most powerful solution in addressing the pandemic learning loss is being overlooked. Implementing county policy to quicken school reopening and providing financial stimulus for underprivileged areas do not seem to have systematically influenced the learning outcomes of high school students. When looking at the coronavirus’s influence on Southern California, the prevailing narrative is wrong at worst, and incomplete at best. In order to most effectively combat Southern California’s learning loss, policy makers should look to address the concerningly high rates of chronic absenteeism that still remain as a residual effect of the pandemic’s virtual learning environment. Our research suggests that the most powerful solution to increasing high school educational outcomes is to get students back in their seats–not quickly, but consistently.

Article by Noah Hendelman 25′ and Meghna Pamula 25′

Economic Journalists

Lowe Institute of Political Economy