The FED Looking Forward

Donald Trump has recently publicly expressed his displeasure with continued rate hikes by the Federal Reserve. In both July and August he criticized the Fed for raising rates, declaring himself “not thrilled” and asserting they should be more accommodative. Will such criticism affect the behavior of the Fed?

There is a long and much-studied history of political pressure on the Federal Reserve. The American people tend to hold the President accountable for the state of the economy—to a degree far beyond his actual influence. Naturally, this leads presidents to reach for any lever in sight in an attempt to boost the economy. In the words of economist Ken Rogoff, “Richard Nixon is the all-time hero” of attempts to push for stimulus on the eve of an election. As the incumbent vice president, Nixon blamed his narrow defeat in the 1960 Presidential elections on the modest recession of that year. And, with his characteristic resentment of the East Coast elite, he blamed the recession on the “financial types” who prioritized raising interest rates to restrain inflation over lowering interest rates to reduce unemployment. Having achieved victory in 1968, President Nixon then proceeded to pressure Fed Chair Arthur Burns to keep interest rates low, stimulating spending and jobs, during the approach to the 1972 elections. Many economic historians believe Burns’ accession to this pressure was a critical precursor of the inflation of the 1970s.

But as a result of hard-won lessons from that episode, the Federal Reserve has changed. Presidential bluster is unlikely to have an effect unless backed up by legislative action from Congress. Following the inflation of the 1970s and the role of pressure from elected officials in letting the genie out of the bottle, macroeconomists came to believe in the paramount importance of a central bank independent from political pressure. While the President appoints the members of the board of governors of the Federal Reserve, they are appointed to 14 year terms which removes the ability of a president to pressure a board member by threatening not to reappoint.

However, the charter and prerogatives of the Federal Reserve as an institution are delineated by Congress and can be changed via the legislative process. In the 1970s, Democratic members of Congress routinely threatened to curtail the powers of the Fed if the Fed did not keep interest rates low. Research from Professor Shelton and Professor Hess found that since the appointment of Paul Volcker, the Fed has consistently resisted pressure from elected officials. Moreover, the lessons of the 1970s have delivered a strong constituency among not just economists and the financial sector, but also many members of Congress for the primacy of keeping inflation low.

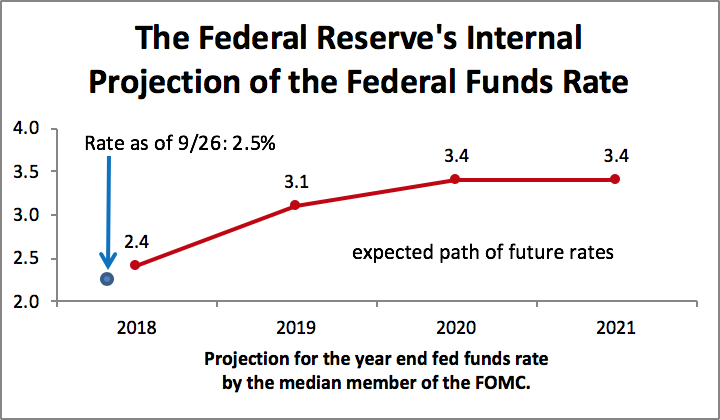

So despite the President’s displeasure, we should expect the Fed to continue to tighten on the schedule they have laid out in their forward guidance (shown in the chart above.) This implies continued strengthening of the dollar and continued downward pressure on the housing market. A stronger dollar, which increases the purchasing power of American citizens and thus increases imports, is likely to boost the activity of LA area ports and thus help the Inland Empire logistics hub. The president may continue to raise tariffs, but is unlikely to have any influence on interest rates.